I was listening to Radio 4's All in the Mind yesterday. It's not a programme I often catch, but I was on a long drive back from talking at Spalding Grammar School, a situation where I tend to give myself up to whatever Radio 4 has to offer. (I even listen to the plays.) Something really strange happened on this programme, which illustrated either the dangers of doing science journalism badly, or the ethical dilemmas facing experimental psychologists.

The story was illustrating how feedback influences sporting performance. Dr Tim Rees of Exeter University was putting forward the idea that positive feedback after failure, emphasing what can be changed rather than what can't improves performance. Although this is vaguely self-evident, it's quite interesting - but the BBC presenter decided to illustrate the theory with an 'experiment.'

The idea was that she was to throw darts at a dartboard blindfolded. She would then be given feedback and they would see how it influenced her performance. Leaving aside this being a meaninglessly small sample, there seemed to be a significant problem with the experimental design. There is going to be a large element of randomness in the outcome, so it is very hard to read anything into what you discover. And this seems to have made them come a cropper.

The presenter threw her first darts and scored 6. She was then given very negative feedback suggesting there was nothing she could change. The implication of what had been said was that she would then do worse. She threw again... and the sound faded out before we heard her results. The obvious implication - she did better on the second throw than the first (statistically quite likely if she got a single dart on the board), but they didn't want to admit it.

Then, to make things even more dubious, at the end of the show she claimed that she scored not 6 but 46 on the first throw. Yet they clearly said 6 - I checked on Listen Again. So there are two possibilities. Either they are fibbing to make the programme give the answers they want - not how we do science, guys, very poor journalism - or the psychologist lied to her when he told her she scored 6, where she actually scored 46. (Remember she was blindfolded.)

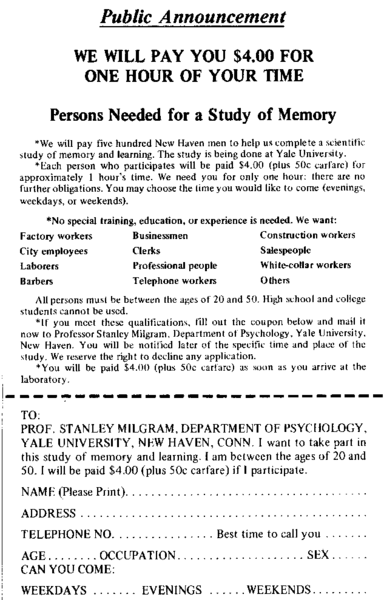

If the latter was true it just joins a whole host of examples where experimental psychologists lie to their participants. There was another story in the same programme of an experiment where one of the subjects in an experiment was a plant, put there to elicit a reaction. And all the way through the history of experimental psychology you hear time and time again 'This is what the subjects thought was happening, but really...' I suppose the classic is the famous Milgram experiment where the subjects thought they were giving electric shocks to a stooge, but really they weren't. (In fact a double lie as they were told it was a study of memory.)

It's entirely possible that the BBC example was just fiddling the figures to get the experimental result they wanted - bad science journalism rather than bad scientists - yet the fact is experimental psychology is solidly based on lying to people, to the extent that I'm amazed anyone intelligent taking part in a test doesn't assume they're lying. (Which may make the test findings increasingly dubious.) Once upon a time it was considered fine to do things to experimental subjects they weren't aware of. Now it's not. You have to make it clear exactly what's going on. So how come psychologists get away with lying all the time? Is it really okay to say 'We can suspend ethics for the duration of the experiment'?

It may well be necessary to get results, but since when has 'The end justifies the means' been a rule of science? Is it time experimental psychology was radically changed? Perhaps so.

The story was illustrating how feedback influences sporting performance. Dr Tim Rees of Exeter University was putting forward the idea that positive feedback after failure, emphasing what can be changed rather than what can't improves performance. Although this is vaguely self-evident, it's quite interesting - but the BBC presenter decided to illustrate the theory with an 'experiment.'

The idea was that she was to throw darts at a dartboard blindfolded. She would then be given feedback and they would see how it influenced her performance. Leaving aside this being a meaninglessly small sample, there seemed to be a significant problem with the experimental design. There is going to be a large element of randomness in the outcome, so it is very hard to read anything into what you discover. And this seems to have made them come a cropper.

The presenter threw her first darts and scored 6. She was then given very negative feedback suggesting there was nothing she could change. The implication of what had been said was that she would then do worse. She threw again... and the sound faded out before we heard her results. The obvious implication - she did better on the second throw than the first (statistically quite likely if she got a single dart on the board), but they didn't want to admit it.

Then, to make things even more dubious, at the end of the show she claimed that she scored not 6 but 46 on the first throw. Yet they clearly said 6 - I checked on Listen Again. So there are two possibilities. Either they are fibbing to make the programme give the answers they want - not how we do science, guys, very poor journalism - or the psychologist lied to her when he told her she scored 6, where she actually scored 46. (Remember she was blindfolded.)

|

| The Milgram experiment |

It's entirely possible that the BBC example was just fiddling the figures to get the experimental result they wanted - bad science journalism rather than bad scientists - yet the fact is experimental psychology is solidly based on lying to people, to the extent that I'm amazed anyone intelligent taking part in a test doesn't assume they're lying. (Which may make the test findings increasingly dubious.) Once upon a time it was considered fine to do things to experimental subjects they weren't aware of. Now it's not. You have to make it clear exactly what's going on. So how come psychologists get away with lying all the time? Is it really okay to say 'We can suspend ethics for the duration of the experiment'?

It may well be necessary to get results, but since when has 'The end justifies the means' been a rule of science? Is it time experimental psychology was radically changed? Perhaps so.

Comments

Post a Comment